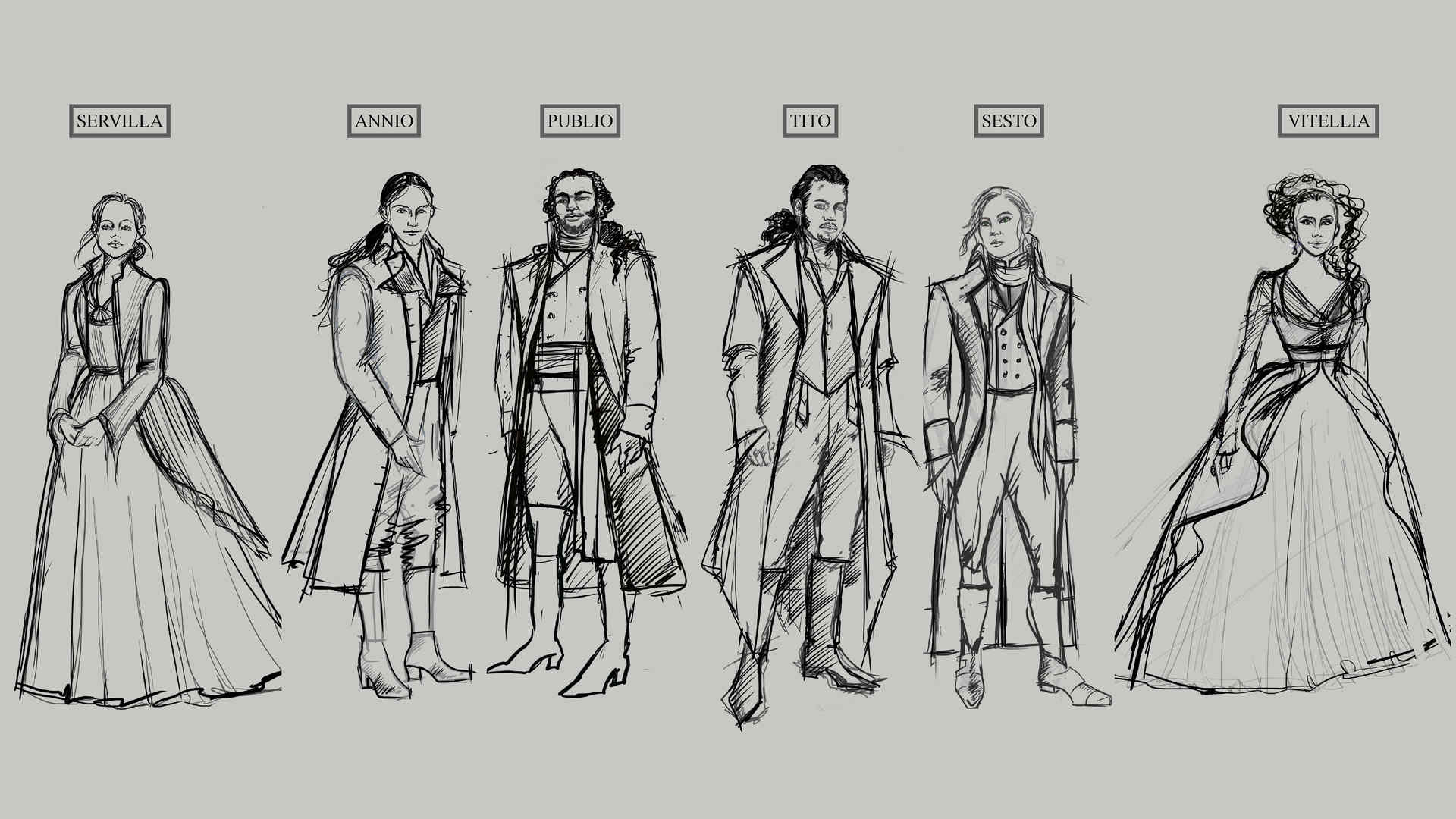

In April, Juilliard Opera presents Mozart’s La clemenza di Tito with alum Nimrod Pfeffer conducting the singers and the Juilliard Orchestra. Faculty member Stephen Wadsworth, who’s directing the production, wrote about the opera.

By Stephen Wadsworth

The French Revolution came together in the fast-moving spring and summer of 1789. After the spontaneous storming of the Bastille by a Paris mob on July 14, a long pent-up energy was released in violence. Over the next three years, that energy grew darker and darker as France marched toward the dismantling of the monarchy in favor of a people’s government—strongly inspired by the American Revolution, which immediately preceded it. The retooling of a centuries-old political system was a complex and tortuous process that brought unrest to every area of European life.

Ironically, La clemenza di Tito, written and premiered in late 1791, was commissioned in mid-July to celebrate the coronation in Prague of a monarch—Leopold II—as King of Bohemia. The situation in France was deeply concerning to other European royals, who tracked it keenly, nervously aware that developments in France might forever alter their own social and political systems. On August 27, as Mozart’s carriage headed to Prague for the coronation, Leopold and King Frederick William II of Prussia issued a proclamation affirming their desire to “put the King of France in a state to strengthen the bases of monarchic government.” On December 3, two days before the Tito premiere, the French king, Louis XVI, confined to Paris by an increasingly powerful revolutionary Assembly, wrote secretly to Frederick William urging a military intervention by neighboring monarchies to restore his authority and “prevent the evil which is happening here before it overtakes the other states of Europe.” To no avail.

Given the urgency of then-current events, it’s surprising that representatives of the Prague government had suggested for the occasion the oft-set libretto by Pietro Metastasio, La clemenza di Tito. They were certainly thinking that a tolerant, beneficent emperor hero with a common touch was just the model for a contemporary coronation, but why did they not remember that the libretto featured an assassination plot, a rebellion, and, moreover, a political betrayal in that emperor’s inner circle? They couldn’t have known the Tito libretto would be trimmed and streamlined by a new librettist, Caterino Mazzolà, and transformed by Mozart into an intense psychological drama focused deeply on the anatomy of betrayal and its personal consequences. Tito, by far Mozart’s leanest, most trenchant opera, surely packed a punch on the night, though there is no reliable report of the court’s reaction.

If Tito was written in the context of a changing, ever less certain Europe, it was written also in the context of Mozart’s last months, at the end of a life increasingly scarred by financial woes, ill health, and the crushing, bewildering disappointment of his once brilliant career prospects. The crisis of faith suffered by confused, questioning Europeans as the Age of Enlightenment was closed down by violent revolution and that suffered by Mozart as his once-promising life grew soberingly limited, are merged and probed in Tito. Mozart reaches imploringly through the characters’ dilemmas for answers to his own existential questions. He was no stranger to loneliness, injustice, and betrayal, but he consistently sought and offered up grace and the sublime.

Tito ends in a C-Major blaze, but for all its Enlightenment-inspired braveries, it seems to me grave and unresolved—not a fairy-tale solution to life’s trials like Die Zauberflöte, which premiered just a few weeks after Tito. Its sobering reality mandated moral responsibility regardless of the cost, in the tradition of 17th-century French playwright Jean Racine, whose tragedy Bérénice must have made it into Metastasio’s hands. The old-school monarchs for whom Tito was written may have approved a hero who bonded intimately with his people and forgave a revolution—but one wonders whether the conflicting personal loyalties of the characters, and the opera’s anxious, urgent portrayal of political change, might have challenged Their Highnesses to deeper acts of tolerance.

When a country is profoundly divided, it is critical to have leaders who can think, weigh, and consider; who can care more about what’s right than about their own comfort; who have a conscience and respect for their people. It was the challenge of 1791 Europe. It is the challenge of 2024 America.

Vocal arts faculty member Stephen Wadsworth is directing this production